I often have to make the same basic points in discussions. I’m putting them down here and in future, I’ll simply link to the relevant one. As I write a lot about gender, that’s the examples I’ll be giving, but the points are more generally applicable.

Reading the whole thing in one go will sound pretty negative, I warn you. That’s not the point, this is reference material to be used in parts at the right time. I just need to publish it at some point.

This is and will continue to be a work in progress, and is a bit rought around the edges. Feedback welcome.

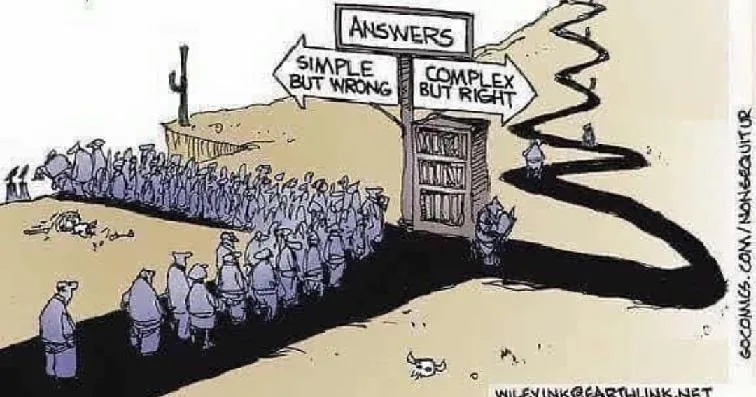

1. The world is not black and white

Are men changing, or are they not changing? Do the feminists care about men or do they not? Is the current heterosexual dating crisis men’s fault or women’s fault?

These are all daft questions. The answer is always: the world is more complicated than that.

Likewise, when I say I don’t think that something is entirely right, it doesn’t mean I hold the complete opposite position.

For example, the fact that I criticise men on specific points does not mean that I hate men and am a feminist lackey. Neither does the fact that I criticise feminists on specific points mean I hate feminists and am an apologist of the patriarchy. There is a range of options in between. I can agree with some aspects but not others. I can think there is a positive but also a negative side.

Black-and-white thinking is a sign of intellectual laziness and a primary tool of populist manipulation.

2. We can do more than one thing at once

It is perfectly possible to acknowledge that there are many problems women face and work to fix them, AND ALSO there are other problems men face that also need fixing. Accepting one does not require you to deny the other.

Fixing problems is not a zero-sum game. There is no need to feel threatened or say things such as: Oh boo-hoo, you struggle with X? Well, we struggle with Y! We can perfectly well work on solving both X and Y simultaneously!

And of course, sometimes one problem is more serious or has a higher priority. But guess what? This doesn’t mean that we should focus 100% on that problem and throw the other in the ditch. We can, like, focus 80% on the more important one, but still do some work on the other.

3. We can disagree and it’s OK

In some disagreements, one side is right and the other is wrong. Maybe they didn’t get their facts right, maybe they have the wrong values, maybe they are making invalid arguments.

It makes sense to show the wrong side that they’re wrong, preferably in a respectful way. Except when they’re being blatantly racist, sexist, or otherwise offensive — no respect for that.

But in many disagreements, there isn’t really an obvious right or wrong. Often, it boils down to conflicting values, e.g. if one person really values freedom but the other values safety, they can have a reasonable disagreement on an acceptable level of state surveillance.

Many disagreements boil down to people’s priorities. If I really care about X but you about Y, we can disagree on what’s the more important thing to do first.

Other disagreements are impossible to resolve due to the world’s annoying complexity. There are multiple sensible paths to gender equality and it is just impossible to tell if the one I want to follow is better or worse than the one you do.

The fact that we disagree on such points does not mean we need to pit ourselves against each other, think less of one another, or fight. We can just, like, live with it.

4. The criticism should be proportional to the fault

If someone makes a blatantly sexist comment, they deserve harsh criticism. But if someone makes a mildly insensitive comment, they don’t deserve to be treated as harshly.

If your criticism is indiscriminately up to 11 at all times, it’s not only unfair — it’s also ineffective because it gives people no indication of how wrong they are and in which direction to change. At some point, they will just go: well fuck it, whatever I say I’ll be battered anyway, so might as well go full steam.

5. Not insulting or invalidating someone doesn’t count as ‘coddling’

Sometimes people will act like big babies who cry the moment you criticise anything they are genuinely wrong about. That’s not OK and should be called out and resisted.

But refusing to dance around somebody is not the same as showing up to gratuitously insult them and invalidate their feelings. One is about coddling, the other: just being a dick.

They’re really not that hard to distinguish. One is about the presence of something, e.g. you’re going out of your way to dance around and coddle someone. The other is about the absence of something, e.g. you’re NOT going out of your way to be a dick to someone.

6. Being supportive of someone is not doing the work for them

Sometimes other people expect you to solve their problems for them. That’s not OK and should be called out and resisted.

But other times, they are actually doing some work already. A lot of the work that the genders expect from one another is really hard. It requires unlearning a lifetime of social conditioning and redefining one’s value system.

Needless to say, having the support of allies is invaluable. Being such an ally is not the same as doing people’s work for them. It’s helping them see the way and offering feedback and incentives to guide them.

Likewise, refraining from standing over them with a stick and criticising their every move also doesn’t count as doing the work for them. It’s just not being a dick.

7. You sure love this stick, did you think about using a carrot, too?

It has been shown time and again that all animals, including humans, respond much better to positive reinforcement than punishment. It’s behaviourism 101.

If somebody is making a range of different comments, some of them problematic, others good and insightful, but you only ever show up to criticise them for the former and never to say anything positive about the latter, you are not making them change for the better.

They will probably get that there’s something wrong where they got the stick, but what they will mainly learn, is that you’re a bully with a stick who should be avoided. They will start disliking you and everything you stand for. Quite likely, they will start doing more things you criticised, just to spite you.

Conversely, offering positive reinforcement for desired behaviours will get them to like you and want to do more things you think are right.

8. The fact that you’re discriminated against doesn’t mean I need to agree with everything you say

Being discriminated against certainly gives people unique experiences and awareness of what it is like to be discriminated against. Often people who are not discriminated against don’t know what it’s like and thus you are way more likely to be right about those things.

But that does not mean you are always right about everything. You can get the facts wrong. You can be expecting too much. You can fail to appreciate how things look from the other side. You can misinterpret other people’s intentions. You can judge someone too harshly.

9. You are making a dishonest argument or committing a logical fallacy

a) Strawman

You are not really arguing against what the other person is saying. Instead, you are arguing against an exaggeration, a caricature which is obviously wrong. But it’s not what they’re saying.

Example: I think feminism and gender theory should pay a bit more attention to men’s issues. What? You want to take feminism away from women and make it all about men?!

b) No true Scotsman

You are excluding inconvenient counterexamples and ignoring inconvenient points by adjusting definitions and distinctions in a way that favours your perspective.

Example: No man would say that! But I’m a man and I say that. Well clearly, you’re not a real man then!

c) Ad hominem

You avoid engaging with the point I’m making and instead try to discredit me to make my point seem wrong or to ignore it.

Example: If men want to succeed in dating, they should put some work into becoming more interesting. Whatever, you’re 6′ tall, obviously it’s easy for you.

d) Kafka Trap

You’re setting your argument or question up in such a way that whatever I say is wrong.

A whole bunch of examples in this article.

10. Debates ae about finding the truth, not about being right

The point of discussing something is not to defeat the enemy and come out looking strong and victorious. The point is to get closer to working out the problem, finding the truth, and to come out smarter.

If your main concern is not losing, you are likely to miss good points, come up with poor arguments, or start rationalising. You might think it makes you look stronger but it really doesn’t, as anyone can see through it.

Very much to be continued…